Introduction

Physiotherapy in Cambridge, Galt, and Preston for Lower Back

Welcome to The Cambridge Physiotherapy's patient resource about low back pain.

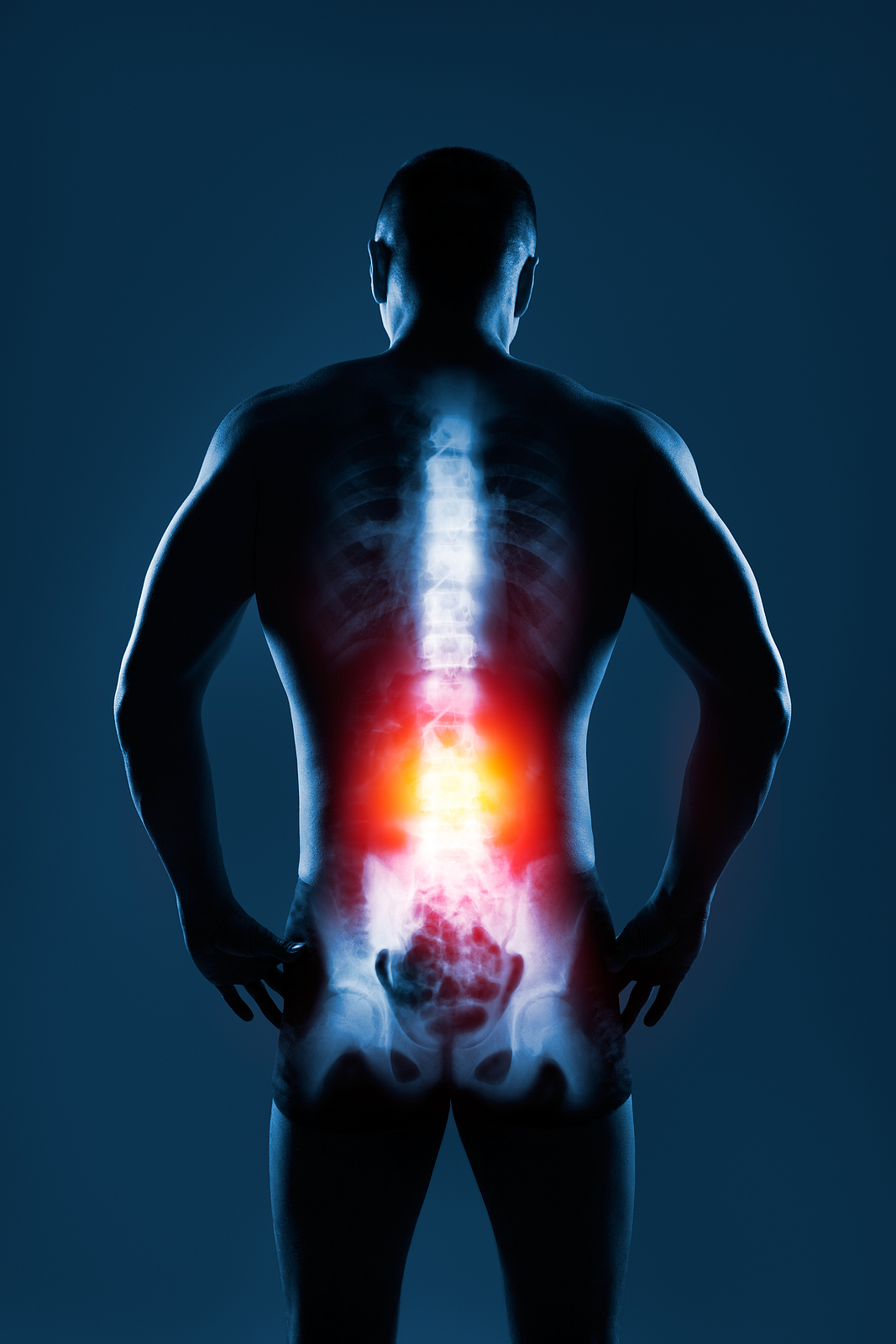

Low back (lumbar) pain is one of the main reasons people visit their doctor. For adults over 40, it ranks third as a major issue—after heart disease and arthritis— that necessitates medical treatment.

Eighty percent of people will experience low back pain at some point in their lives. Furthermore, nearly each individual who suffers from this problem will endure recurring low back pain.

Very few people who feel pain in their low back have a serious medical problem! Ninety percent of people who experience low back pain typically report that their symptoms usually resolve in 2-6 weeks. In addition, experiencing a bout of back pain does not usually mean your condition will develop into a chronic back issue.

For moderate or severe pain that persists or becomes debilitating, the temporary use of pain relievers and physiotherapy may help provide lasting relief.

This guide will help you understand:

- The anatomy of the spine and low back

- What causes low back pain

- What the most common symptoms are

- How health care professionals diagnose back pain

- how to manage your pain and prevent future problems

#testimonialslist|kind:all|display:slider|orderby:type|filter_utags_names:Back Pain|limit:15|heading:Hear from some of our patients who we treated for *Back Pain*#

Anatomy

What Makes Up the Lumbar Spine?

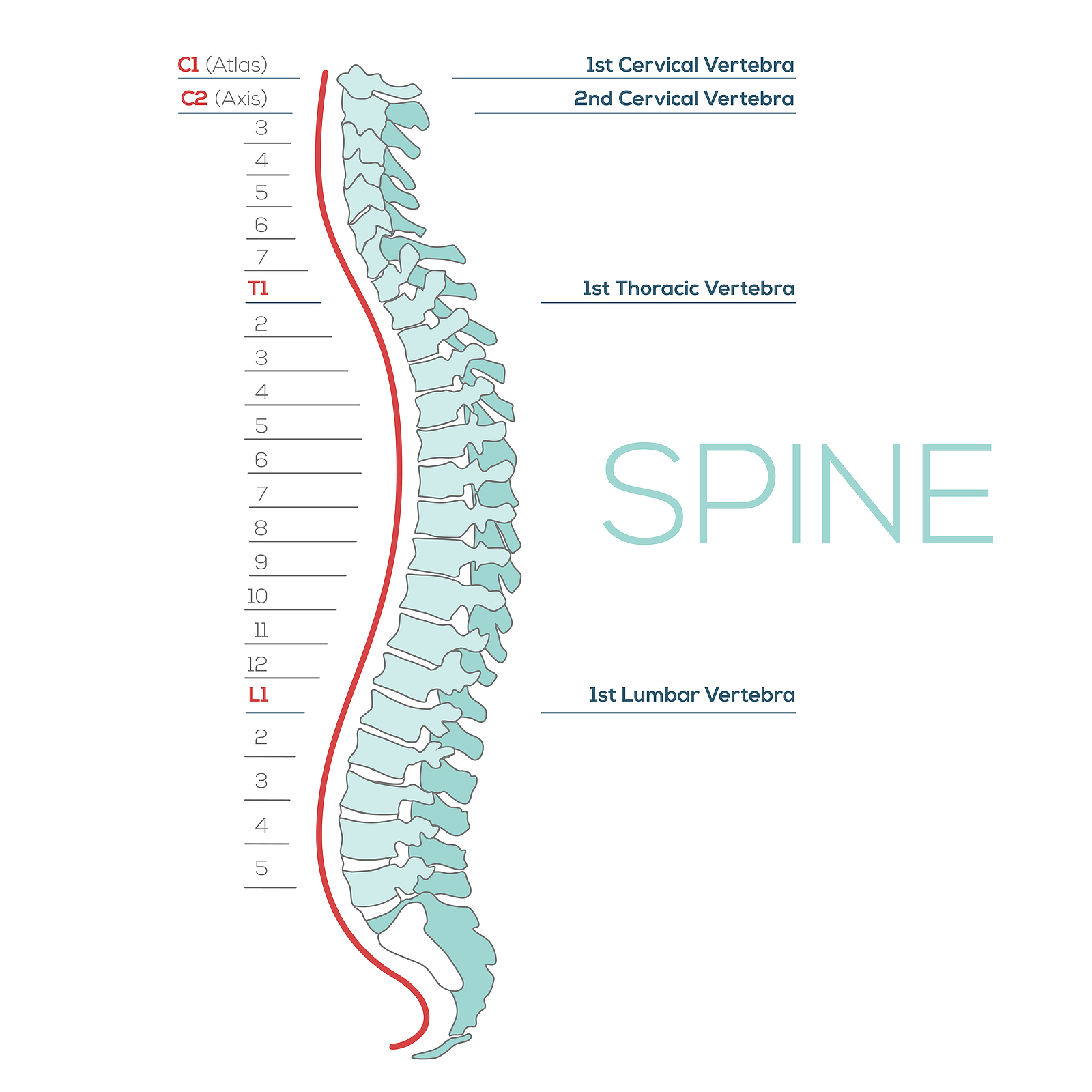

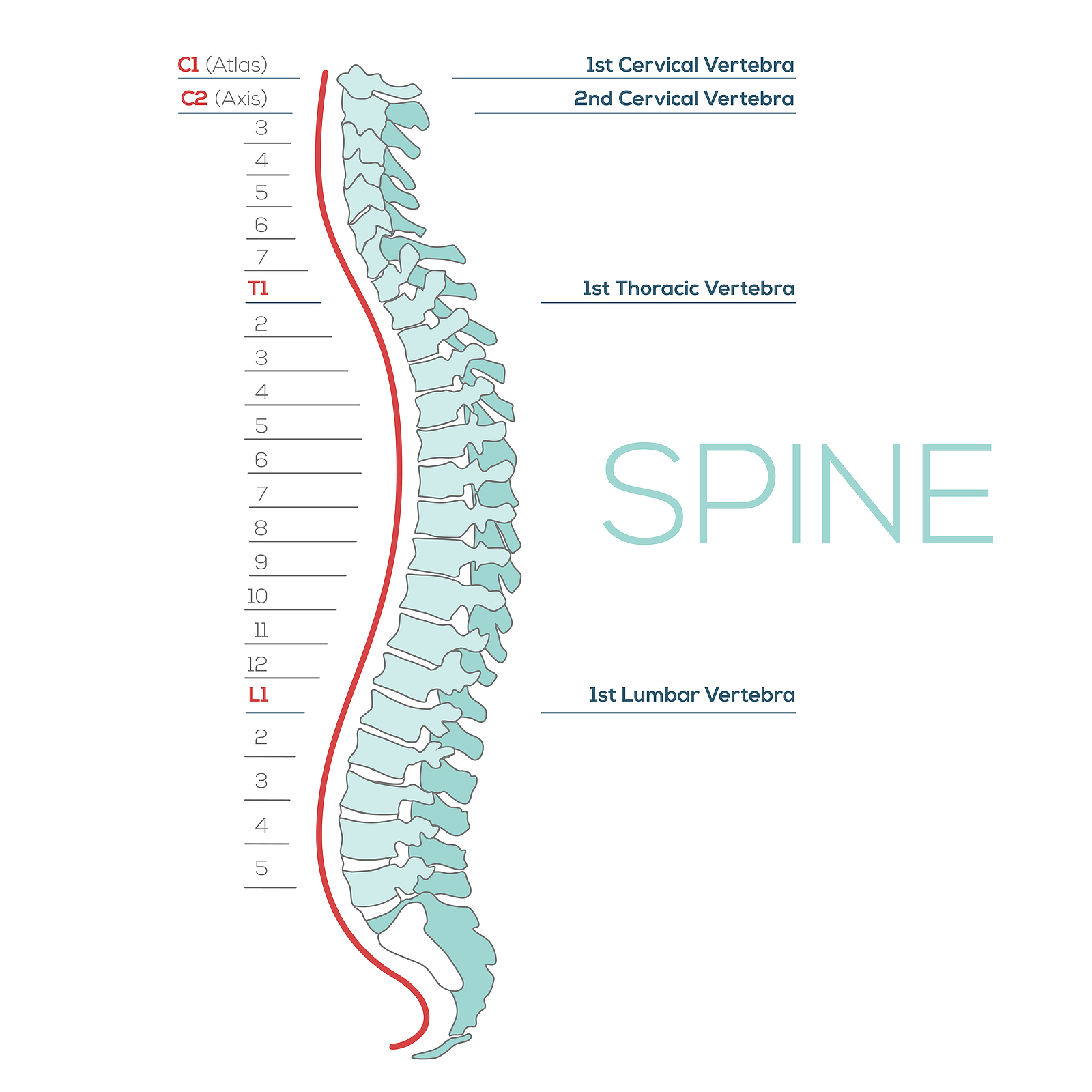

The human spine is made up of 24 spinal bones, called vertebrae, as well as the sacrum and the coccyx. The sacrum is a triangular bone near the bottom of the spine and the coccyx is more commonly known as the tailbone.

Vertebrae are stacked on top of one another to create the spinal column. The spinal column gives the body its form and helps sustain an upright position.

The lumbar spine—where pain is often experienced—is made up of five vertebrae positioned near the bottom of the spinal column. Doctors often refer to these vertebrae as levels L1, L2, L3, L4 and L5. The ‘L’ refers to ‘lumbar’. The lowest vertebra, L5, is connected to the top of the sacrum—a triangular bone at the base of the spine that is located between the two pelvic bones. Some people are born with an extra or sixth lumbar vertebra called L6. Having an extra vertebra doesn't usually cause physical problems.

The main portion of a vertebra is a circular segment of bone called a vertebral body. This structure supports about 80% of the body's weight load while an individual is standing. Vertebral bodies are also the point of contact or attachment for the spinal discs located between vertebrae. The lumbar vertebral bodies are taller and bulkier than the vertebrae in the cervical and thoracic regions because the lower back is designed to withstand more pressure and weight during daily activities such as lifting, carrying, and twisting. The bulkier vertebral bodies also provide support that allows the large, powerful muscles attached to or near the lumbar spine to work effectively.

The second portion of the vertebra is a body protrusion called the spinous process. This is that hard bony structure you feel when you run your fingers down the back of your spine. The vertebral body and the spinous process are joined together by vertebral arches. The arches form a ring that enclose the spinal cord and cerebrospinal fluid. Vertebrae are also connected by fibrous facet joints that are located on each side of the spine. The joints improve the stability and flexibility of the spine. The stacked formation of vertebrae along the spinal column forms a long, hollow tube that protects the spinal cord.

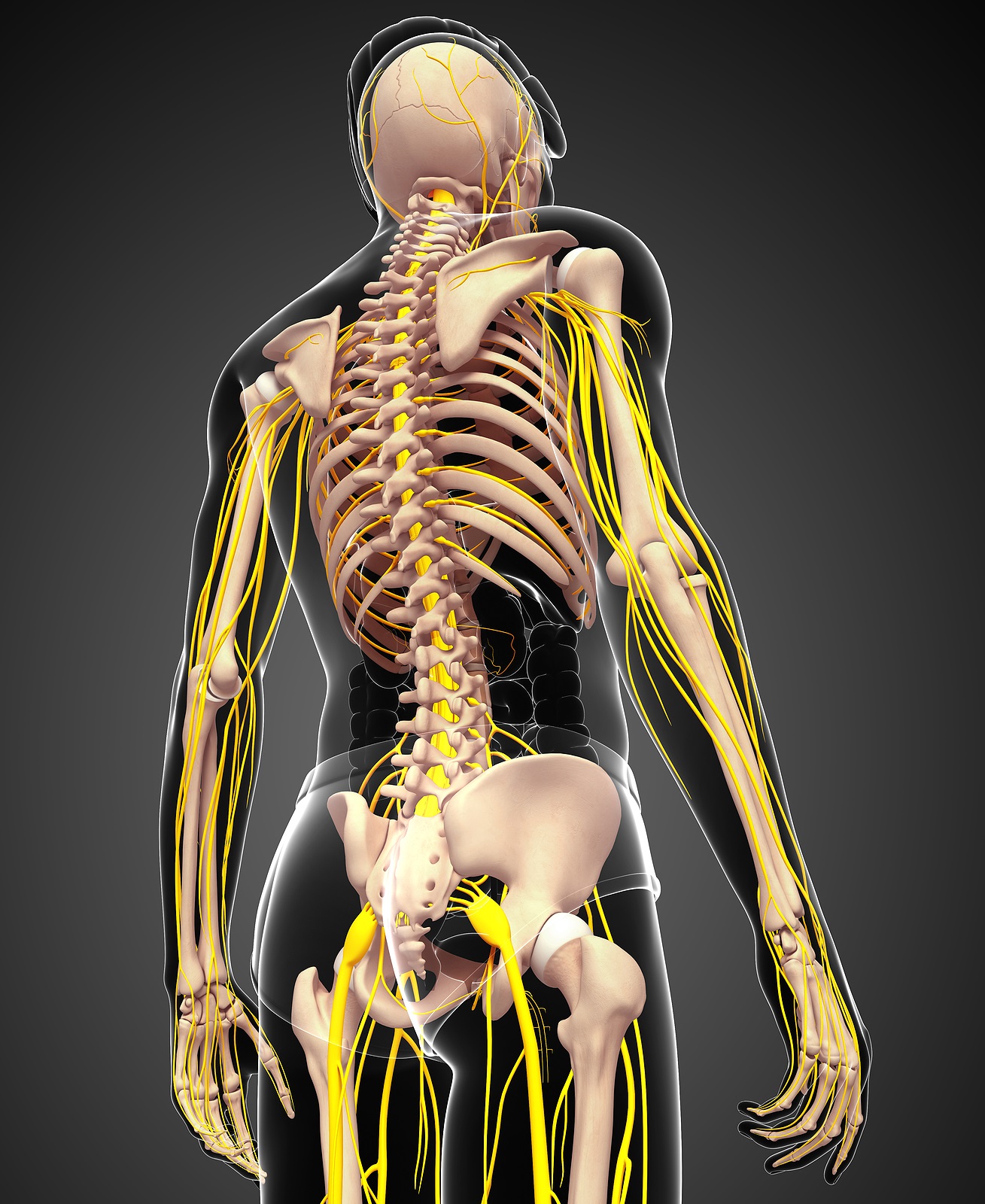

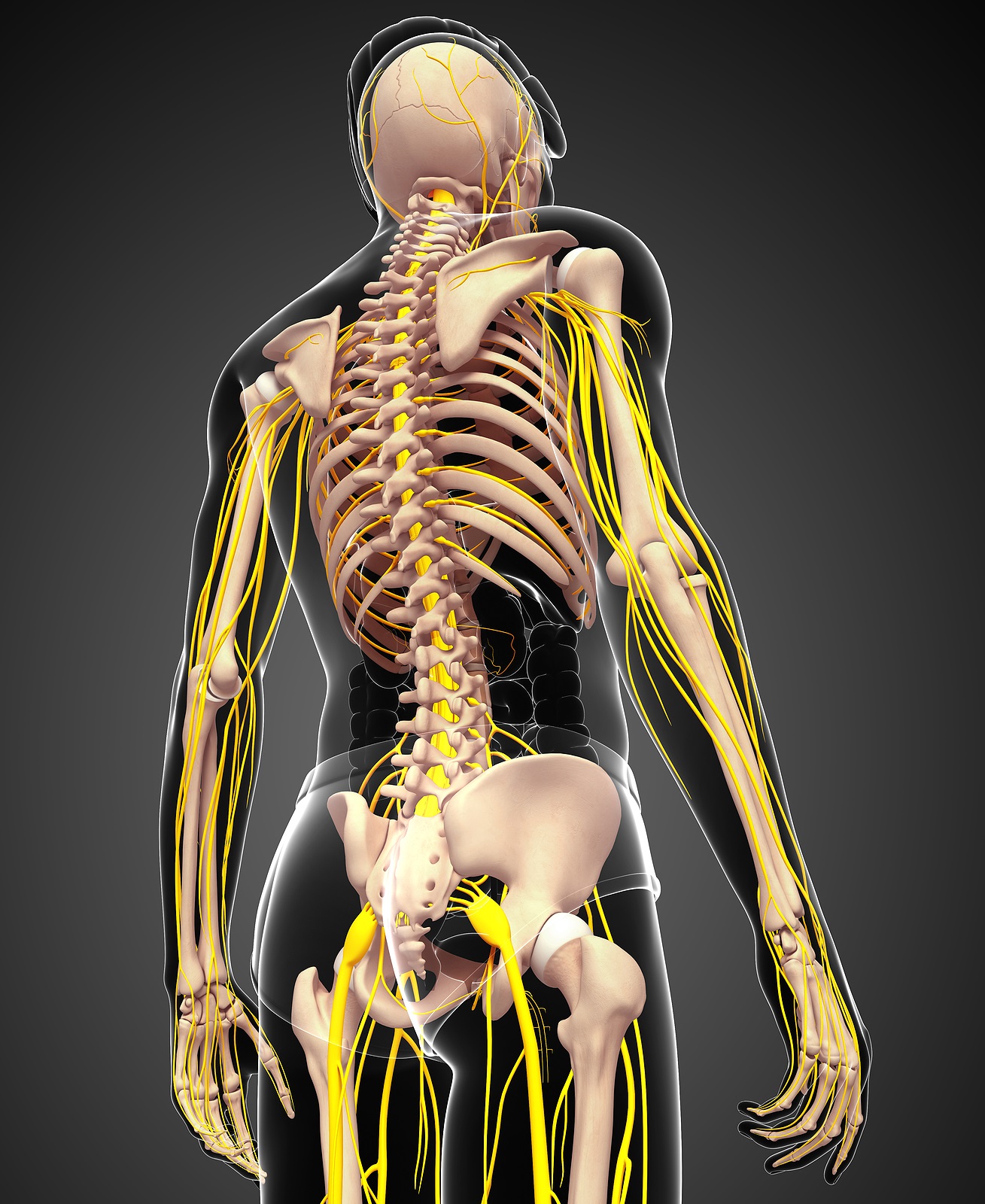

The spinal cord originates at the base of the brain and travels down the spine through the hollow tube formed by the vertebral arches into the L2 vertebra. Below this level is a bundle of nerves that further extend downward and travel to the pelvic organs and lower limbs. This bundle of nerves is called the cauda equina. In Latin, this term means ‘horse’s tail’ because it resembles the strands of a horse’s tail.

The spinal cord also consists of nerve roots that extend from the sides of vertebrae. Networks of nerve roots allow long nerve fibers to travel throughout the body and form the body’s electrical system. The nerve roots and fibers along the cervical spine extend to the neck, shoulders, arms, and hands. The nerves in the thoracic spine travel into the chest and abdomen. Nerve roots that originate in the lumbar spine consist of nerve fibers that travel to the lower regions of the body such as the pelvis, hips, thighs, legs, and feet.

How the Spine Works

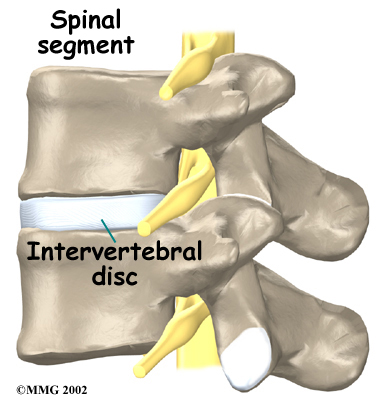

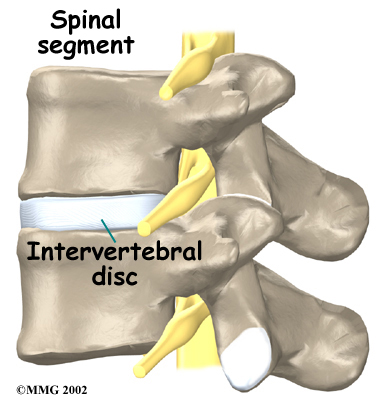

It is sometimes easier to understand how the spine works by looking at a spinal segment. A spinal segment consists of two vertebrae separated by an intervertebral disc, the nerves that leave the spinal cord at that level, and the small facet joints that link each level of the spinal column together.

The intervertebral discs normally work like shock absorbers. They protect the spine against the daily pull of gravity. They also cushion the spine during strenuous activities that put extensive pressure on the spine, such as jumping, running, and lifting.

An intervertebral disc is made up of two parts. The center, called the nucleus pulposus, is spongy and provides most of the disc's ability to absorb shock. The spongy center is also designed to transmit force and resist rotation. The nucleus pulposus is held in place by the annulus, which is found on the outside of the disc. The annulus is a series of strong ligamentous rings. Ligaments are strong connective tissues that attach bones to other bones. These ligaments form a criss-cross layer of protective tissue around the middle of the disc (the nucleus pulposus). The criss-cross formation is significant, as only half of the ligaments engage when the spine rotates to one side, while the ligaments on the opposite side remain stationary. The same activity occurs when the spine is rotated in a different direction. The criss-cross structure of the ligaments that make up the annulus provide maximum support, resistance, and flexibility of the spine.

There are also two facet joints—one on each side of the spine—that connect two stacked vertebrae in a spinal segment. Facet joints are located along the sides of the entire spine, from the neck down to the sacrum. The pattern and alignment of the facet joints in the lumbar region allow the spine to easily bend forward and backward. The anatomy of the lumbar spine also allows a certain degree of rotation, but not as much as the spinal segments in the cervical or thoracic spine. As the lumbar spine rotates, the facet joints squeeze together on one side and slightly expand on the other side to facilitate spinal movement.

The surfaces of the facet joints are covered by articular cartilage. Articular cartilage is smooth, rubbery tissue that covers the ends of most joints. It allows the ends of bones to move against each other smoothly without causing painful friction between bones that come in contact with one another.

In addition to facet joints on the sides of the spine, there are two spinal nerve roots that exit the sides of each spinal segment, one on the left and one on the right. As the nerve roots leave the spinal cord, they pass through a small bony tunnel on each side of the vertebra, called a neural foramen.

Spinal segments along the entire spine, including the lumbar spine, are heavily supported by ligaments and muscles that tremendously reinforce their strength capabilities. Ligaments—that enhance stability by attaching bones to bones—are arranged in various layers and run in multiple directions. Thick ligaments connect the bones of the lumbar spine to the pelvis and the sacrum (the bone below L5).

The muscles of the lower back are also arranged in layers. The deepest layer of muscles is located along the back surface of the vertebrae. These deep muscles coordinate their actions with the muscles in the abdomen (the core) to help hold the spine steady during activity.

A specific group of muscles called the erector spinae muscles also make up one layer of the lower back muscles. These long muscles run up and down the spine, from the chest and lower ribs down to the bottom of the back. You can easily feel your erector spinae muscles at the bottom of your back protrude outward slightly if you stand on one foot and then lift one leg backward. The long muscles twist together in the lumbar spine to form a thick, wide tendon sheath near the bottom of your back—called fascia—that connects the bones of the low back, pelvis, and sacrum. This fascia provides substantial support for the lumbar spine, especially when the spine bends forward.

Causes

Why do I have low back pain?

There are many causes of low back pain and health care professionals are not always able to pinpoint the exact source of each patient's pain. Although the exact cause of the pain may be hard to accurately identify, most back pain can be effectively treated based on symptoms and knowledge about how structures in the back and spine usually respond to certain activities.

Acute tissue damage, such as a torn muscle, an irritated disc, a pulled ligament, or a spinal fracture will cause acute (short-term) back pain. Most back pain of this nature usually heals within 6-12 weeks of the injury. For some individuals, the recovery period may be shorter than six weeks. Repetitive activities of daily living, when performed correctly, actually keep the spine strong! However, inactivity, prolonged sitting, or repetitive heavy loading with improper mechanics or poor efficiency can mean the lumbar spine is subjected to more load, rotation, or strain than it can normally withstand. This type of issue can lead to an acute injury, or more localized degeneration (wear and tear) than would typically occur with age. Gradual degeneration of back and spinal tissue does occur with age, but the aging process alone is not usually the direct cause of back pain. Persistent or chronic back pain may also be associated with other contributing factors such as systemic inflammation, stress, tension, or fatigue.

There is strong evidence that smoking cigarettes, for example, accelerates degeneration of the spine, specifically the flat part of the vertebrae called the vertebral endplate. This can cause a vacuum type of phenomenon in which the intervertebral disc begins to shrink or be pulled inward against a vertebra, causing decreased disc height between the vertebrae. Scientists have also observed hereditary links among family members, which shows that genetics plays a role in how fast degenerative changes in the spine may occur.

Degeneration

Under healthy conditions, the intervertebral disc adapts to different spinal movements. The disc is spongy and firm, and like most cartilage it actually gets stronger in response to increasing loads! Health care professionals used to believe that cartilage damage was caused by a “wear and tear” issue, but now understand that it is actually a “wear and repair” phenomenon where the body’s natural repair processes may weaken over time. This means you should not be afraid of increasing the load on your spine when proper mechanics are used. Furthermore, the nucleus in the center of the disc contains a great deal of water. This gives the disc its ability to absorb shock and help the spine withstand heavy and repeated forces.

Normal structural changes in the disc occur with age, but this does not typically lead to pain. However, the annulus that surrounds the nucleus of the disc weakens and begins to develop small cracks and tears over time. The disc also begins to lose some of its protective fluid, causing it to shrink in size and height. As the disc continues to degenerate, the space between the vertebrae decreases. This compresses the facet joints along the back of the spinal column. As these joints are forced together, extra pressure builds on the articular cartilage on the surface of the facet joints. In combination with local or systemic inflammation, this extra pressure can damage and sensitize the facet joints. If this issue progresses, arthritis may develop in the facet joints.

These degenerative changes in the discs, facet joints, and ligaments may cause the spinal segments to move more than they usually do, requiring the muscles to work harder to distribute force and keep the spinal column supple and strong. Extra movement is not always an issue, however—think of a gymnast’s or circus performer’s degree of spinal mobility! Nonetheless, extra movement within the bones and ligaments without strong, supple, conditioned muscles may lead to poor force distribution and frequent episodes of muscle, joint, or ligament sprain.

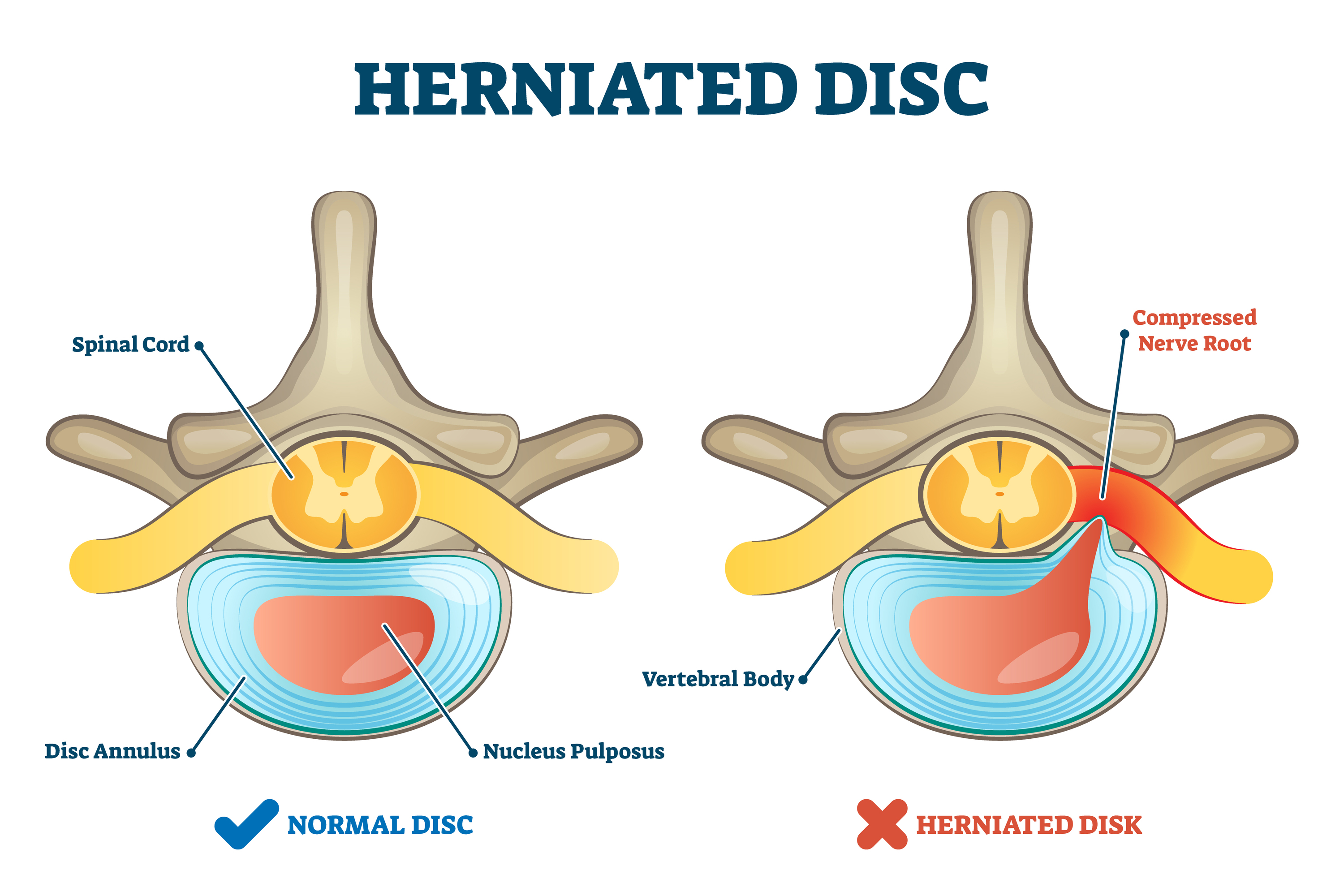

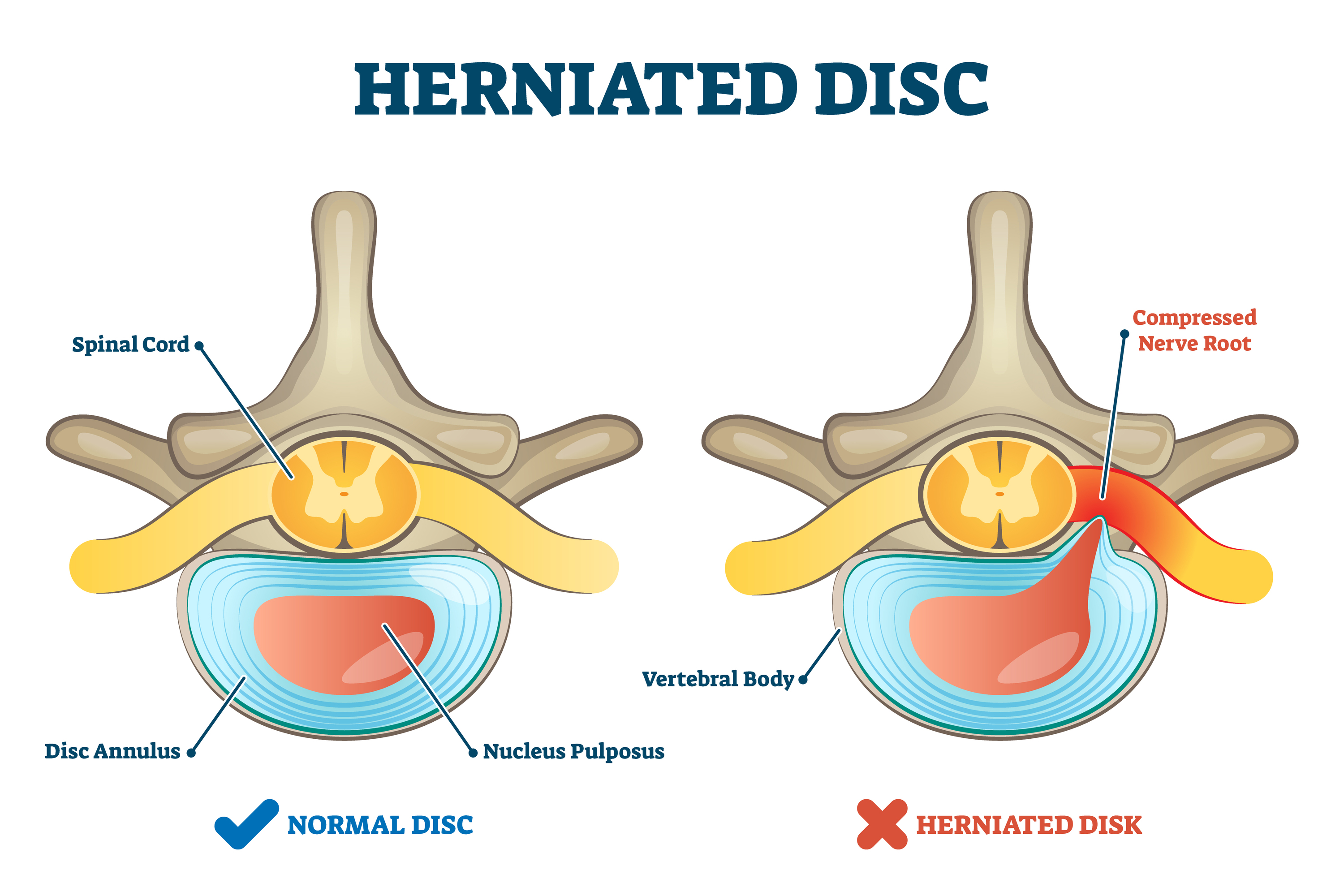

In some cases of degeneration, the nucleus of the disc may push through a torn annulus, toward or into the spinal canal, or into the space where the spinal nerves are located. This is called a herniated or ruptured disc. Sometimes patients refer to this as a slipped disc. The disc material that squeezes out may directly press against the spinal nerves. The disc tissue that pushes through also releases enzymes and chemicals that produce inflammation in the area. The inflammation caused by the chemicals released from the disc often, but not always, causes the transfer of pain signals to the brain. Pressure on the nerves may cause additional sensitization or breakdown of the protective sheath around the nerves.

As the degeneration continues, the body naturally tries to adjust to the disc damage as well as the extra motion the degeneration is causing. In response to the extra movement, the body may develop bony outgrowths around the edges of the disc and facet joints to try to redistribute the load and make the joint more stable. These bony outgrowths are called bone spurs, or on an x-ray report they may be referred to as osteophytes or facet hypertrophy. These bone spurs may not cause symptoms or they may create nerve sensitivity by pressing on the nerves and blood vessels in the spine as they pass through the opening in the vertebra (neural foramina). Bone spurs may also limit normal motion. In addition, the pressure around the nerves may cause pain, numbness, and weakness in the lower back, buttocks, lower limbs, and feet.

Over time, a spinal segment that has degenerated and become more mobile (as described above) eventually becomes stiffer and even less mobile. The ligaments thicken, facet joints enlarge, and disc tissue dehydrates in a continued attempt to adapt to the structural changes and maintain efficient force distribution. Typically, a stiff spinal segment doesn't cause as much pain as a segment that moves around too much. As a result, this stage of degeneration may actually lead to pain relief for some people.

Understanding Types of Pain

Pain research is ever-evolving. The most current guidelines divide pain into a few key categories. The key message is that although pain is a complex perception, all pain is real. It’s a form of signal output from the brain in response to messages from the body. The full definition states that pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with or resembling that associated with actual or potential tissue damage. Back pain commonly falls into all the categories below, which can help explain what may be causing low back pain,, why back pain is so intense at times, or why it lingers.

Nociceptive Pain

This is pain that is produced in proportion to the messages coming to the brain from the tissues that are irritated, damaged, inflamed, or are experiencing mechanical overload. For example, you would expect to feel immediate pain after dropping something heavy on your foot, but it should resolve in a reasonable amount of time if serious damage did not occur. This pain also generally follows a predictable pattern, such as the pain you feel after an acute back muscle spasm. Your back may feel fine while sitting down, but may begin to hurt when you transition to standing. The pain may be milder in the morning and predictably stronger in the evening or following certain activities. The key feature of this type of pain is that it doesn’t last beyond 12 weeks—even though that might not be what your experience feels like.

Neuropathic Pain

This type of pain arises from specific damage or the disruption of the somatosensory system, which is the network of nerves throughout the brain and body that allow you to sense touch, temperature, muscle stretching, and body position. This system is also responsible for taste, hearing, vision, and smell. When neuropathic pain develops, it may be a prolonged experience beyond 12 weeks, where signal transfer to and from the brain gets disrupted. Irritated nerves can also become so sensitive that they may stimulate pain signals in the absence of new tissue damage. Fears and emotions can also contribute to this type of pain, but that isn’t always the case. In cases of low back pain, neuropathic pain occurs when a nerve exiting the spinal column gets inflamed or damaged. Most of the time, the pain will travel down the legs along the path of the nerves involved.

Central Sensitivity or (Nociplastic Pain)

This type of pain arises from altered perception of the messages coming from the body, despite there being no clear evidence of actual or threatened tissue damage, or clear evidence of a disease or disruption of the body’s sensory system (the somatosensory system). This pain is very real, it’s just not necessarily coming from newly damaged tissue or an area that hasn’t healed properly. This type of pain often occurs in the back and usually lasts longer than 12-16 weeks. It is believed that messages from the body that normally wouldn’t create a pain response become amplified within the central nervous system (CNS). These types of pain signals are strongly influenced by thoughts, fears, perceptions, emotions, and environmental triggers. There is also strong evidence that individuals with neuropathic pain will have elements of central sensitization (nociplastic pain) as well.

Many patients with back pain may have a mix of two or more of the types above.

The good news is that all types of pain typically respond to treatment. A health care professional needs to recommend the appropriate form of treatment for the type of pain you are experiencing!

Spine Conditions

Common Spinal Conditions

Complications from back injuries or spinal degeneration can lead to specific spinal conditions. These include:

- Annular tears

- Internal disc disruption

- Herniated disc

- Facet joint arthritis

- Segmental instability

- Spinal stenosis

- Foraminal stenosis

Annular Tears

The structure of our intervertebral discs change with age, much like our hair turns gray. Perhaps the earliest stage of degeneration occurs due to tears that occur in the annulus. These tears can result from natural tissue changes over a period of time or they can be the result of a sudden injury to the disc due to an awkward twist or increased strain on the disc that leads to damage of the annulus. Annular tears may cause pain in the lower back until they heal and form scar tissue.

Internal Disc Disruption

Multiple annular tears can lead to a weakened disc. Furthermore, the disc that sits between two vertebrae naturally dehydrates and shrinks in size (height) over time. This process can accelerate due to a cumulative injury. A cumulative injury is a work-related injury that develops due to repetitive movements. The loss of disc height causes the vertebrae to compress closer to one another. The collapsing disc may be a source of pain because it has lost the ability to offer efficient shock absorption between the vertebrae—a condition known as internal disc disruption. This type of problem primarily causes mechanical back pain due to inflammation of the disc and surrounding structures. However, the disruption of the normal disc anatomy can also add pressure to the nerves in the area and may result in neuropathic pain. In many cases, the body reacts to a collapsed disc by growing small bony outgrowths (bone spurs) near the edge of the disc or the small joints nearby (facet joints) to contain the splaying of the disc. Bone spurs can cause pain by pressing on nearby nerves, blocking their passage, or squeezing nerve roots when an individual tries to move the back naturally.

Herniated Disc

A weakened disc may herniate (shift out of place) or eventually rupture. If the annulus of the disc tears or ruptures, the material in the nucleus can squeeze out of the disc or herniate. A disc may herniate a little or a lot, and the symptoms will vary accordingly. A disc herniation usually causes compressive problems if the disc presses against a spinal nerve. The chemicals released by the disc may also inflame the nerve root, causing pain in the area the nerve travels to such as the pelvis, lower back, or legs. If this type of pain travels down the back of the leg, it may be referred to as sciatica.

Disc herniation occurs more often in younger populations (20-50 years old) when the disc is plump and well hydrated. Poor mechanics while lifting heavy objects or making repetitive movements (bending, twisting, and lifting) can place too much pressure on the disc. The increased pressure can cause the annulus to tear and the nucleus to rupture into the spinal canal.

Facet Joint Arthritis

The facet joints along the back of the spinal column link the vertebrae together. They are not meant to bear much weight, but instead allow free, flexible, and coordinated movement of the spine. If a disc loses its height as it degenerates, the vertebra above the disc begins to compress toward the one below. This causes the facet joints to press together and bear more weight. Joint (articular) cartilage covers the surfaces where these joints meet. Just as with other joints in the body that are covered with cartilage, such as the hip and knee, the facet joints can develop osteoarthritis if the articular cartilage wears away over time due to systemic or local inflammation. Extra load and localized inflammation of the facet joints, such as that from a collapsing disc, can speed up degeneration in the facet joints. The swelling and inflammation from an arthritic facet joint can be a source of low back pain.

Segmental Instability

Segmental instability means that the vertebral bones within a spinal segment move more than they should. This movement can develop if the disc or the facet joints have degenerated and the neuromuscular system wasn’t able to adequately compensate. Usually the supporting ligaments around the vertebrae have also stretched over time, and fail to support the joint as it normally would.

One form of segmental instability is a condition called spondylolisthesis, where one vertebral body begins to slip forward over the one below it. When a vertebral body slips too far forward it can cause lower back problems. Firstly, slipping of a vertebra can lead to mechanical pain simply because the structures of the spine move around too much and become inflamed. The abnormal movement can also cause nerve pain symptoms if the spinal nerves are squeezed during movement. This is common in young athletes such as gymnasts who train hard without ideal efficiency or proper mechanics while their skeleton is immature. In addition, some people are born with spondylolisthesis that doesn’t present until adulthood. This condition may also occur due to repetitive microtrauma or serious sudden trauma.

Stenosis

Spinal Stenosis

Stenosis means narrowing of a specific structure. Spinal stenosis refers to a condition in which the tube-like area (spinal canal) surrounding the spinal cord becomes narrow or closes in. This usually occurs due to bony spurs encroaching on the area, but may also develop from other issues such as cysts or tumors. The spinal cord ends at L2 of the lumbar spine. Below this level, the spinal canal contains only the spinal nerves that come from the spinal cord. These nerves travel to the pelvis and legs. When stenosis leads to narrowing of the spinal canal, either the spinal cord or the spinal nerves coming from the cord are squeezed inside of the canal. The pressure on the nerves or spinal cord can disrupt the way the nerves work. Depending on whether it is the spinal cord being compressed or the nerves, and which nerves are being compressed, resulting problems can include pain and numbness in the buttocks, genitalia, and legs. Weakness may also arise in the muscles of the lower body that are supplied by those nerves.

Foraminal Stenosis

Spinal nerves exit the spinal cord between the vertebrae in a boney tunnel called the neural foramen. Stenosis can also occur in this region and cause this tunnel to become smaller or collapse due to disc degeneration. Bone spurs may also form in the area. This subsequently squeezes the spinal nerve as it passes through the tunnel— a condition called foraminal stenosis.

Symptoms

Symptoms from low back problems vary. The pain or symptoms they experience depend on a person's overall health condition, which structures are being affected, and many other factors like stress, sleep, diet, mood and their beliefs about their pain or condition. Some of the more common symptoms of low back problems are:

- Low back pain

- Pain spreading into the buttocks and thighs

- Pain radiating from the buttock to the foot

- Back stiffness and reduced range of motion

- Muscle weakness in the hip, thigh, leg, or foot

- Sensory changes (numbness, prickling, or tingling) in the leg, foot, or toes

In some rare cases, symptoms may involve changes in bowel or bladder function. These symptoms are caused by a large disc herniation or tumor that pushes straight back into the spinal canal and puts pressure on the nerves that go to the bowel and bladder. In addition to loss of control of the bowel and bladder, the pressure on these nerves may cause symptoms of low back pain, pain running down the back of both legs, and numbness or tingling in the saddle/genitalia area. Pressure on these nerves is considered a medical emergency as it can lead to permanent paralysis of the bowel and bladder. This condition is called cauda equina syndrome. Immediate surgery to remove pressure from the nerves is required.

Diagnosis

How will my health care provider find out what's causing my problem?

The diagnosis of low back pain begins with a thorough history of your condition. Your physiotherapist will ask you questions to find out when you first started having problems, what makes your symptoms worse or better, and how the symptoms affect your daily activity. Your answers will help guide the physical examination. A physiotherapist may also ask you to fill out a questionnaire describing your back problems.

After assessing your medical history, your physiotherapist will physically examine the muscles and joints of your low back and ask you to move in different directions to determine how your pain is affected. It is important that your physiotherapist understands how your back is aligned, finds out where it hurts, and checks which movements improve or worsen your symptoms.

Your physiotherapist may also perform some simple tests to check the function of the nerves in your back. These tests are used to measure the sensation, reflexes, and strength in your legs or feet. The information from your medical history and physical examination will help your physiotherapist decide what else needs to be evaluated during the examination.

Most people with low back pain will NOT need x-rays or other tests to diagnose and treat their pain. In some cases, if an x-ray or other diagnostic could be helpful, your physiotherapist will refer you to a doctor for further diagnostic imaging.

Once your physical examination is complete, your physiotherapist at The Cambridge Physiotherapy will discuss treatment options with you that will help speed your recovery, so that you can return to your normal lifestyle as quickly as possible. It should be noted again that in many cases, one distinct, single structure that is causing your back pain may not be identified. Low back pain is rarely that simple. However, even if one specific structure cannot be identified as the cause of the pain, this does not mean physiotherapy might not be beneficial. On the contrary, most cases of low back pain can be resolved or effectively managed with consistent physiotherapy treatment. The treatment regimen will be structured to your individual needs, such as who you are (e.g., age, gender), how your body moves, what your health beliefs are, and what kind of life you live.

The Cambridge Physiotherapy provides physiotherapist services in Cambridge, Galt, and Preston.

Our Treatment

What can be done to relieve my symptoms?

Physiotherapy can be very effective at easing your current pain and getting you back to your normal everyday activities. This is because physiotherapy has proven to be beneficial for both acute and chronic back pain. Furthermore, physiotherapy can assist patients of all ages and at all stages of back pain, whether this is your first bout of pain, or you have had several bouts and are now experiencing chronic pain. In addition, physiotherapy can help by educating you about how to prevent back pain flare-ups in the future.

Although the time required for rehabilitation varies among patients, you should expect to participate in therapy for anywhere from three weeks to four months, depending on whether your problem is acute or is a chronic issue. The recommended treatment will also depend on how painful and debilitating your back pain is.

Even though back pain can be scary and physically restricting, it is very rarely a sign of serious tissue damage or a dangerous underlying condition. In the majority of cases, back pain responds very well to physiotherapy treatment. Each of our treatment approaches are designed specifically for your individual type of back pain. Furthermore, the main goals include working toward easing your pain, improving your mobility, strength, and posture, and enhancing back function. In addition, your physiotherapist at The Cambridge Physiotherapy will teach you how to control your symptoms and how to protect your spine for many years ahead.

If your low back pain is an acute flare-up of less than 2-3 weeks, your physiotherapist may initially use ice, heat, ultrasound, electric muscle stimulation, interferential current, laser, needling (acupuncture), or hands-on treatment to address your symptoms. These modalities may be particularly helpful during the early weeks to improve your comfort so you can more easily. Adhering to your physiotherapy regimen is an optimal way to quickly get back to your normal activities. Pain education will also be an important aspect of your therapy right from the start, as it can help you understand the nature of your low back pain. In addition, understanding the anatomy of the back and factors that contribute to back pain can help address your fears or beliefs about back pain. Furthermore, engaging in physiotherapy can reduce apprehensions regarding your prognosis, help improve self-empowerment, and decrease the likelihood of developing chronic pain.

Your physiotherapist will also teach you ways to position your spine for maximum comfort while you recover from your injury or flare-up. Your back is designed to withstand a variety of postures and it is healthy for your back to frequently move into many different postures. As long as you are without pain at the time, slouched sitting as well as lifting items with a slightly rounded back are okay for your back! The anatomical structures that support your spine can still work efficiently in these postures. You and your physiotherapist may explore your preferred directions of movement and how to use them to your advantage as you heal. As rehabilitation progresses, it will be very important to explore and practice all directions of movement, and your therapist will guide your individual journey to movement freedom. Your physiotherapist will also explore efficient sitting, standing, and movement postures as well as techniques that help you rediscover the strength and resilience of your spine.

At times, you may be tempted to stop all activity because of your low back pain. It is important to avoid inactivity, as there is a great deal of evidence that shows how beneficial aerobic exercise such as walking, running, or biking helps in the treatment of low back pain. Increased overall fitness also reduces the risk of developing back pain again. Furthermore, moderate to severe pain during activity should always be addressed, but mild discomfort may occur as you start to resume your activities and as your back recovers. Minor discomfort that lingers as you return to daily activities does not mean you are further injuring structures in your back. Intense activity may need to be discontinued temporarily, but gradually returning to your regular routine will be good for your back and your overall health in the long run. Your physiotherapist can help you determine the best activities to start with and the most appropriate way to perform them with your particular injury. The physiotherapist can also assist you in deciding how hard you should push your activity level at each stage of your rehabilitation.

In addition to getting back to regular aerobic exercise, your physiotherapist will teach you specific strengthening and stretching exercises to help your back. Your hip range of motion and strength is particularly important in helping your back function properly, so the physiotherapist will assess your hips and lower body alignment to demonstrate the ideal strength and mobility exercises for your individual needs. These types of exercises address tightness, weaknesses, and side-to-side imbalances.

Your ‘core’ muscles are located around your abdomen and trunk. They help maintain flexible (not rigid) stability in this area. These muscles also ensure efficient load transfer to the lower back and the entire spine. Maintaining adequate core strength is important for anyone, but particularly for those with low back pain. Some patients with chronic back pain unintentionally ‘overuse’ or inappropriately use their core muscles, and this can be more detrimental to someone with back pain than an individual who is not regularly active. Your physiotherapist will check your core activation and strength to teach you how to appropriately and efficiently use your core muscles to support your spine during daily activities. A key aspect of therapy will be teaching you how to move without holding your breath to allow you to engage these muscles efficiently and with less pain. Remember that your back is anatomically designed to withstand the loads of everyday life such as bending, twisting, jumping, and lifting heavy objects. Your physiotherapist will educate you on proper postural movements to ensure you are taking the right steps to optimize your back’s abilities.

If you have severe back pain, the physiotherapist may choose to work with you in a pool or encourage you to do exercises in a pool on your own. Physiotherapy performed in water puts less stress on your low back, and the buoyancy allows you to move more easily during exercise. Clients consistently report how much easier it feels to move their back when they are in the water.

It is well known that other factors can drastically affect your chances of getting low back pain and also how quickly you heal from your discomfort. As mentioned previously, people who smoke have both a higher risk of experiencing low back pain and recovering from it more slowly, as smoking decreases the blood supply to tissues and bones. Decreased blood flow leaves tissue vulnerable to injury, accelerates degeneration, and delays healing. Your physiotherapist will encourage you to stop smoking if you currently smoke. Even temporarily quitting while you are addressing your back pain helps, but quitting for good is highly recommended.

Apprehensions, emotions, and personal beliefs also heavily influence the experience of back pain and the recovery trajectory. If you believe your back is unstable, fragile, or undergoing degenerative changes, it will be hard to trust that guided movement is safe. Furthermore, if someone in your family has lived with horrible back pain, you may be inclined to believe that this is also your fate. This is another factor that can influence your experience. In addition, if you have experienced back pain and recovered from it, you may feel similar sensations and discomfort again if you experience emotional trauma, loss, or anxiety. Your physiotherapist is aware of these factors and may perform additional assessments to determine if your pain is being created by the brain, rather than in response to tissue damage. In either case, your physiotherapist knows the pain you experience is real and that you are not suffering from intangible pain. Treatment approaches for centralized (or nociplastic) pain may be targeted at restoring your sense of safety, exploring your beliefs about your back pain in a non-judgemental way, and possibly getting you additional support to help process the emotional strain.

Being overweight can also affect your lower back, particularly if you carry your weight around your abdomen. This indicates a higher body fat percentage and therefore higher systemic inflammation. If appropriate, your physiotherapist will encourage you to lose weight and modify your eating, sleep, and exercise patterns, which will help you recover more quickly and avoid future flare-ups.

Physiotherapy at The Cambridge Physiotherapy will focus on reassuring you that swiftly getting back to work and other normal activities won't cause you harm and can actually help improve your back’s tolerance for activity in the future. Nonetheless, back injury flare-ups may occur in the future and are often related to a period of emotional trauma, low mood, poor mental health, disrupted sleep, stress, inactivity, or trying a new activity. Your physiotherapist will discuss what steps to take if your back pain returns.

Your physiotherapist can also show you how to keep moving with efficiency during routine activities. You'll learn about healthy postures for your back and using the best body mechanics to assist your back while lifting and carrying, standing and walking, and performing work duties. The anatomical structure of the back naturally accommodates activities such as carrying heavy loads, as well as sitting and standing for periods of time. Contrary to popular belief, a slouched sitting position and allowing your back to bend forward slightly while lifting items is actually conducive to how your back is designed and is considered proper body mechanics! These positions allow the layers of long and tough ligaments and muscles at the back of the spine to do their job in supporting the spine. In addition, our bodies are made to move instead of staying in one position for too long, especially when recovering from injury. Your physiotherapist can guide your movements as you recover from your back pain.

Bed Rest

Although ‘bed rest’ was a common prescription in the past for acute back pain, ‘bed rest’ or lying down and remaining stationary is rarely prescribed to help back pain these days. Alternatively, in cases of severe pain, your physiotherapist may suggest a short period of ‘modified rest’ where you are encouraged to rest in a comfortable position, such as on your back with your knees supported or in a semi-reclined position in a chair. Modified rest permits moderate activities, such as gentle hip and back exercises within the normal range of motion or light walking to keep your back moving while allowing your acute pain to settle. Staying in one position for too long, although it may feel comfortable at the time, is actually detrimental to healing. For this reason, modified rest after an acute injury will only be recommended for no more than 2-3 days.

Back Braces

A back support belt is sometimes recommended when back pain first strikes. In many cases, a back brace can help provide support by adding compression to your back and increasing your confidence when you move. A brace can also lower the pressure inside a problem disc, decrease pain, and allow you to engage in some activities longer than you could without the back brace. Your physiotherapist will gradually encourage you to discontinue wearing the brace as your pain improves and you can engage in more advanced back strengthening exercises. Using the brace routinely after recovering from acute pain is not recommended. Wearing a back brace all the time after your back has recovered may cause muscles to atrophy (shrink) and some patients will psychologically begin to rely on the belt instead of on the strength of their own muscles.

Medications

Your physiotherapist will suggest that you consult with your doctor or pharmacist regarding the use of pain relief or anti-inflammatory medication for your acute back pain. Although there is no medication that will cure low back pain, short-term medications that combat pain, inflammation, and muscle spasms may be useful supplements for your rehabilitation program. Over-the-counter medication is sufficient for most cases of back pain and helps support restful sleep. Persistent back pain is often linked to sleep problems.

The Cambridge Physiotherapy provides services for physiotherapy in Cambridge, Galt, and Preston.

Physician Review

Diagnostic Tests

In a number of low back pain cases, no special diagnostic testing is required to diagnose and treat your back pain. Your doctor or physiotherapist will be able to determine what the most probable cause of your pain is from the history of your injury, how you are moving, and from the physical exam. The exact structure causing the pain in your back may be unknown, but this does not preclude treatment to help your pain. A combination of irritated connective tissues, muscles, joints, ligaments, discs, and nerves in the back is often the culprit, so ‘diagnosing’ or naming one single structure is usually futile. Treatment to help your back problem can still be effective without knowing the exact anatomical cause of your pain.

When acute back pain occurs, diagnostic tests are not routine, as diagnostic tests that are completed unnecessarily may produce misleading findings. In numerous interesting studies, patients have demonstrated major structural changes in different back or spinal structures on x-rays in the absence of physical symptoms.

Diagnostic testing for back pain is reserved for cases where:

- The pain is not acting as your physiotherapist or doctor would expect

- Your symptoms aren’t resolving with the usual conservative treatment

- Your pain is intense and relentless

- Your pain is affecting your normal functions

- Your symptoms include nerve pains in your leg and foot

You have a suspected serious problem, such as cauda equina syndrome, which refers to disc disruption that is affecting the nerves supplying your bowel and bladder

Radiological Imaging

If diagnostic tests are deemed necessary, there are several different tests that your doctor may recommend. Radiological imaging tests allow your doctor to see the anatomy of your spine, which assists the determination of what may be causing your back pain. Knowing what structures may be contributing to your back pain may help further direct the most appropriate treatment to assist you.

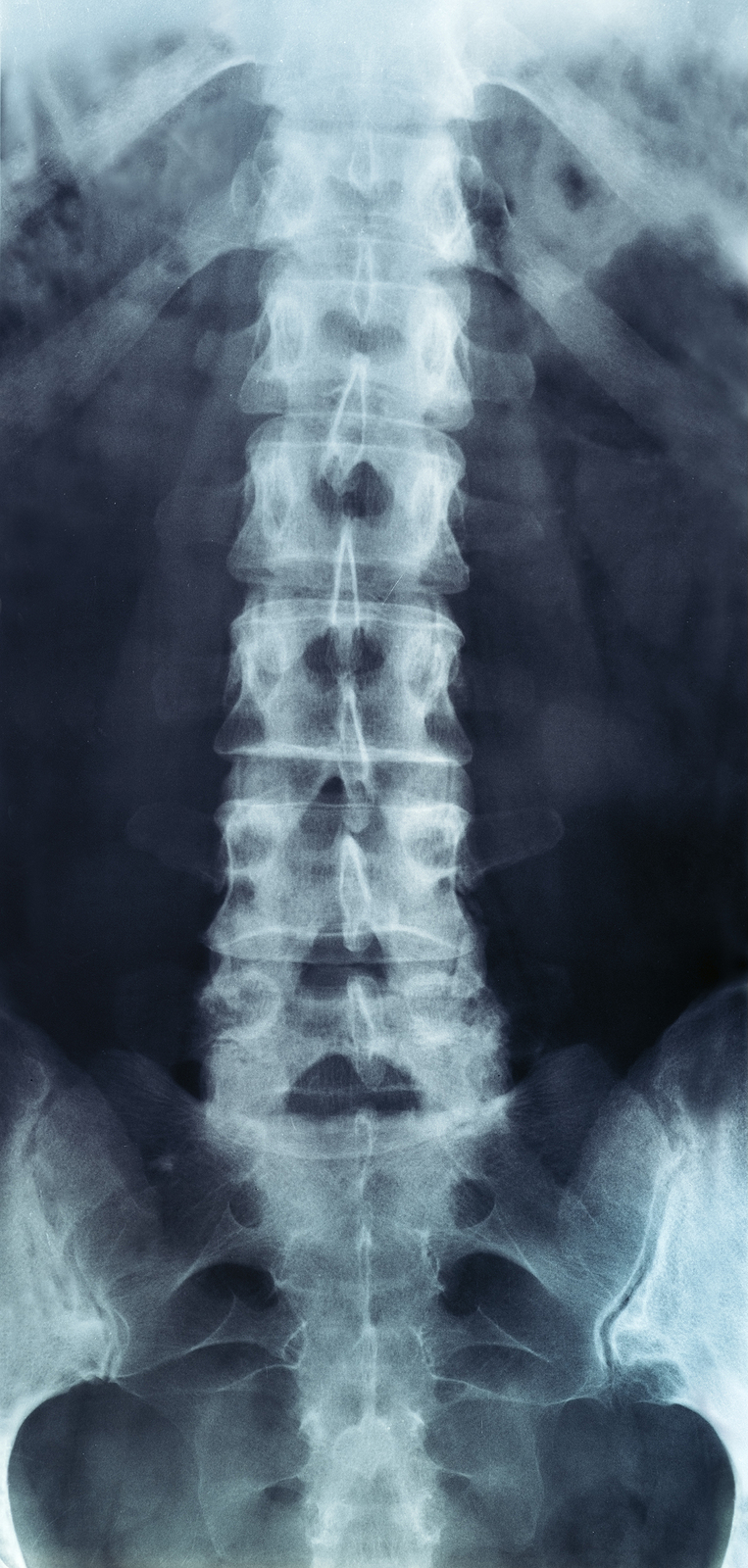

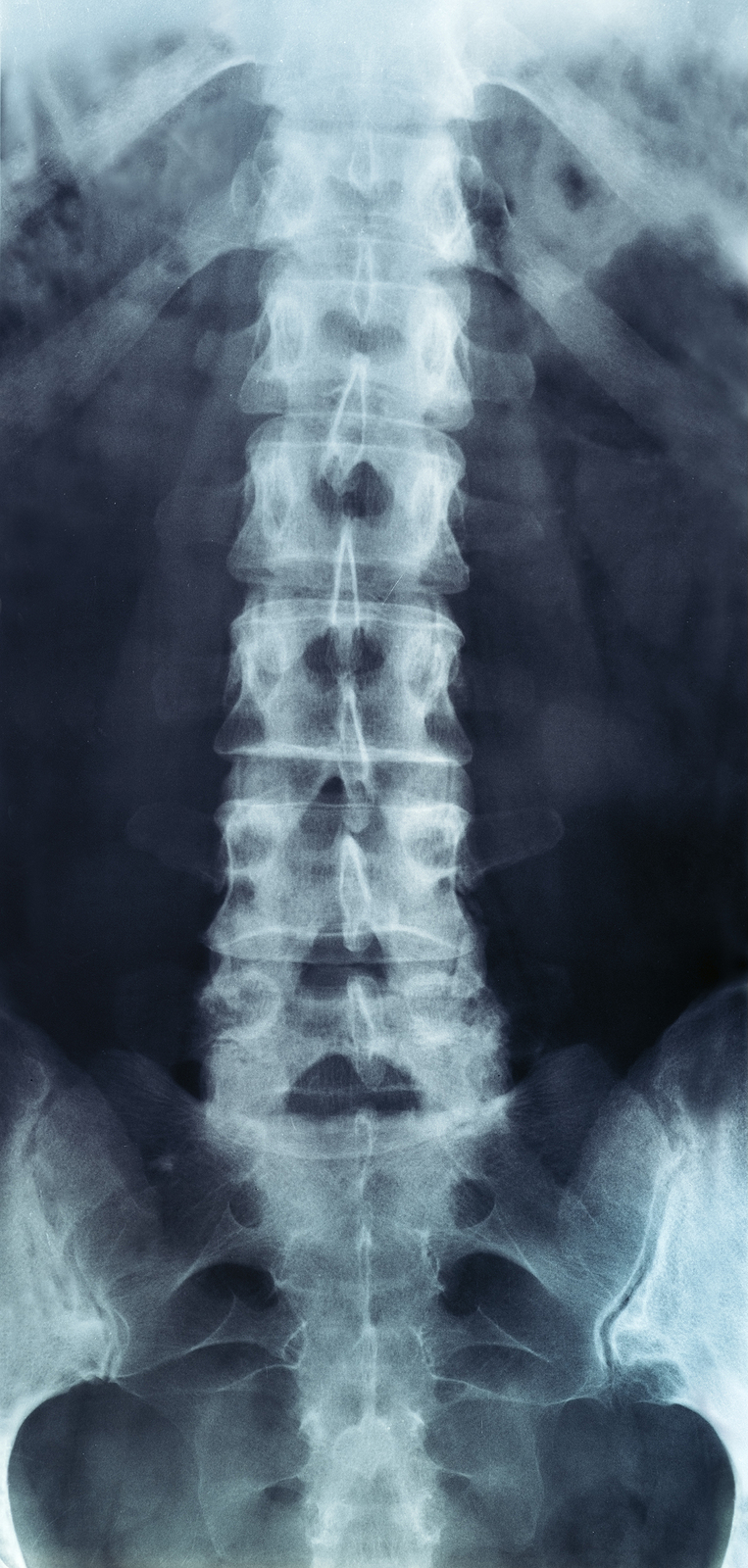

X-rays

X-rays are usually the first test ordered before any of the more specialized tests are completed. X-rays use electromagnetic radiation to show problems with bones and can also reveal problems such as fractures, infections, or bone tumors. X-rays of the spine can give your doctor information about bone alignment and can demonstrate how much degeneration has occurred in the spine. Both alignment and degeneration can affect the amount of space in the neural foramina and between the discs, which subsequently impacts the nerves in the area. This is important information your health care professional can use to establish a treatment plan.

Flexion and Extension X-rays

Special x-rays called flexion and extension x-rays may help to determine if there is true instability between vertebrae. These x-rays are taken from the side as you bend as far forward and then as far backward as you can. Comparing the two x-rays allows the doctor to see how much motion occurs between each spinal segment.

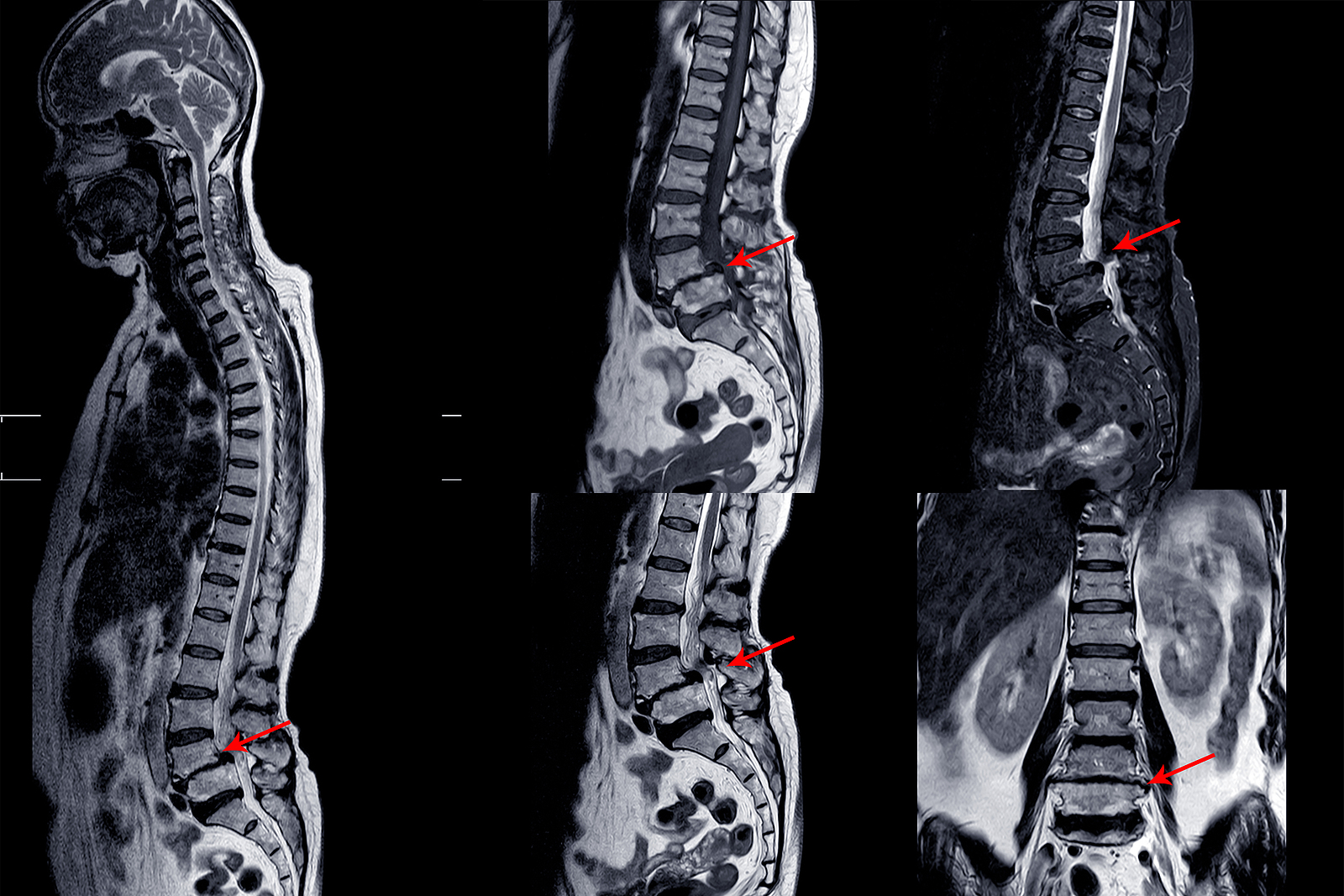

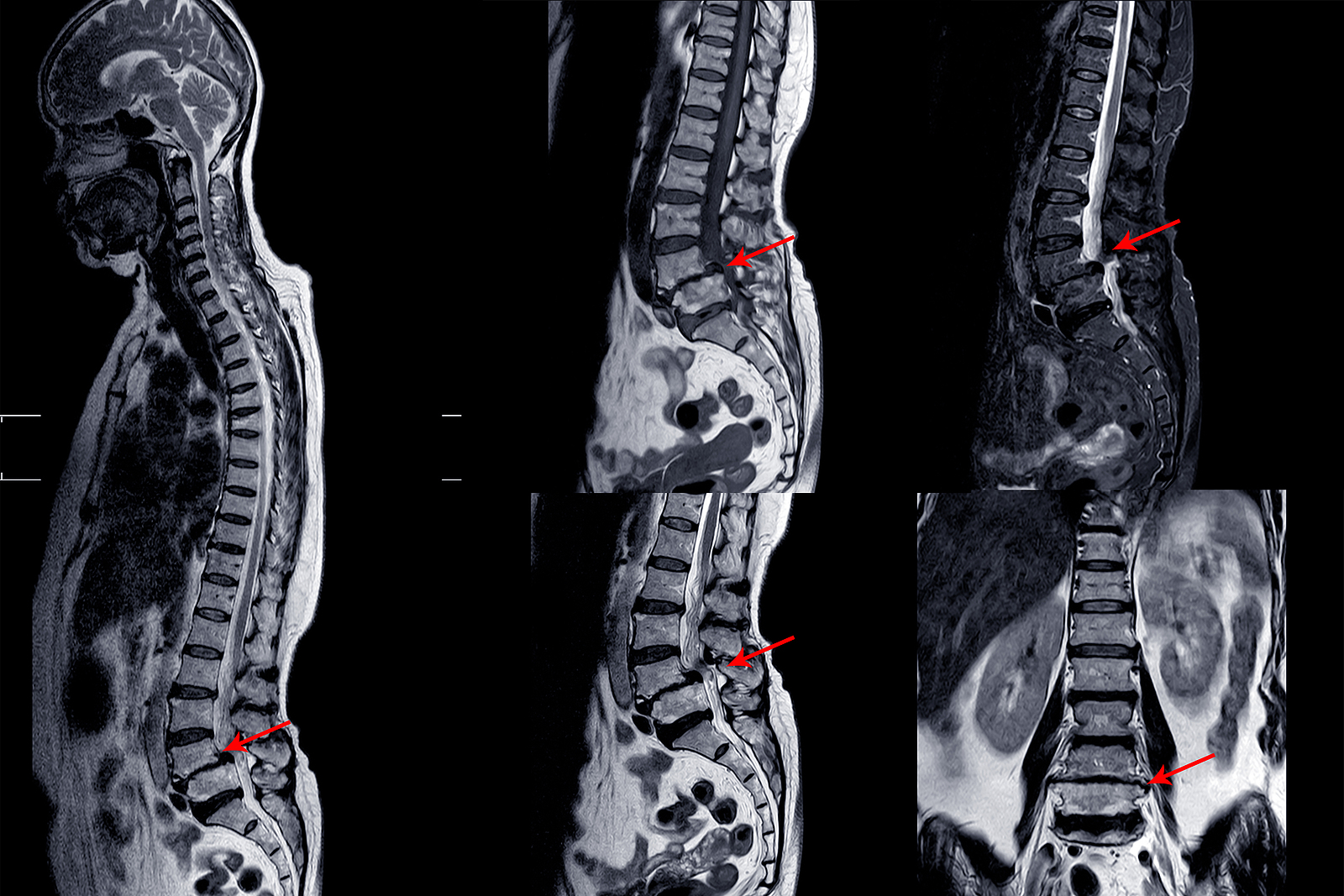

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

An MRI scan uses magnetic waves (not radiation) to create pictures of the lumbar spine in sections called slices. The MRI scan shows the bones in the lumbar spine as well as soft tissue structures such as the discs, joints, and nerves. MRI scans are painless and don’t subject you to radiation as an x-ray does. MRI scans are the most common test for visualizing the lumbar spine after an x-ray has been taken. These tests may be recommended if your health care provider is concerned that surgery may be necessary.

In some cases, specialized MRIs that involve an injection of contrast dye may be recommended by your doctor to see specific structures. These special MRIs are performed following the intravenous injection of gadolinium-based dye. The contrast dye enhances image quality and can define some structures more than a regular MRI.

Computed Tomography (CT) Scan

A CT scan is a special type of x-ray that lets doctors see thin sections or slices of tissue. The machine uses a computer and a series of x-rays to create these slices. CT scans subject patients to significantly more electromagnetic radiation than a traditional x-ray, so this type of test will only be ordered when truly necessary to help diagnose a problem. CTs can be useful for the visualization of bones, soft tissues, and blood vessels.

Myelogram

The myelogram is a special kind of x-ray or CT scan where a dye is injected directly into the spinal canal to look for problems in this area. Myelograms are used to help diagnose herniated discs, pressure on the spinal cord or spinal nerves, spinal tumor, or bone spurs that may be pressing on the spinal canal structures.

Discogram

The discogram is another type of specialized x-ray. A discogram has two stages. First, a needle is inserted into the problem disc and then saline is injected to create pressure inside the disc. If this injection reproduces your pain, it suggests that the disc is the source of your problem. During the second part of the test, dye is injected into the disc. The dye can be seen on an x-ray. Using both regular x-rays and CT scan images, the dye outlines the inside of the disc. This can show abnormalities of the nucleus such as annular tears and ruptures of the disc.

Bone Scan

A bone scan (skeletal scintigraphy) specifically diagnoses problems with your bones. During a bone scan, a safe and small amount of a radioactive tracer is injected into your veins. This tracer is taken up by your bones. The tracer illuminates on special diagnostic images taken of your back. The tracer builds up more in areas where bone is undergoing a rapid repair process, such as a healing fracture or the area surrounding an infection or tumor. A bone scan may initially be used to locate a problem, then additional tests such as a CT scan or MRI can be used to look at the area in more detail.

Electromyogram (EMG)

An EMG is a special test used to determine if there are problems with any of the nerves traveling from the spinal cord to the lower limbs. EMGs are usually performed to determine whether the nerve roots have been pinched by a herniated disc or structurally damaged by inflammation. During the test, small needles are placed into certain muscles that are supplied by each nerve root. If there has been a change in the function of the nerve, the muscle will not fire properly and this discrepancy will be noted. Furthermore, an EMG can help determine which nerve root is involved. Often, the nerve disruption has to be significant to show a change on an EMG.

Additional Tests

Not all causes of low back pain are from conditions within the spine itself. Other conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthropathies, or an infection may lead to a back problem. Pain may also be referred from issues such as gastrointestinal distress, stomach ulcers, kidney problems, and aneurysms of the aorta. Blood tests, urinalysis, or additional tests may be needed to rule out problems that do not involve the spine.

Physician Treatment

In certain low back pain cases that don’t respond to physiotherapy, more aggressive forms of treatment may be required in addition to your active mobility and strengthening program. These are temporary measures and interventions designed to provide short-term relief that allows you to move more and build up your conditioning as well as load tolerance.

Injection-Based Treatments

Spinal injections are used for both diagnostic purposes as well as treatment. There are several different types of spinal injections that your doctor may recommend. Most injections use a mixture of an anesthetic and some type of cortisone (anti-inflammatory) preparation. The anesthetic is a medication that numbs the area where it is injected. If the injection takes away your pain immediately, this provides important information suggesting that the injected area is indeed the source of your pain. The cortisone component in the injection decreases inflammation and can reduce the pain from an inflamed nerve or joint for a prolonged period of time.

Some injections are more difficult to perform and require the use of a fluoroscope. A fluoroscope is a special type of x-ray that allows the doctor to see a real-time x-ray image continuously on a TV screen during the procedure. The fluoroscope is used to guide the needle into the correct place before an injection is administered.

Epidural Steroid Injection (ESI)

Back pain from inflamed nerve roots and facet joints may benefit from an ESI. During this procedure, the medication mixture is injected under fluoroscopy into the epidural space around the nerve roots. Generally, an ESI is only administered when other non-operative treatments aren't working. ESIs are unfortunately not always successful in relieving pain. If they do work, they may only provide temporary relief.

Selective Nerve Root Injection

This type of injection places steroid medication around a specific inflamed nerve root. A fluoroscope is used to guide a needle directly to the affected spinal nerve root, which is then bathed with the medication. In difficult cases, the selective nerve root injection can also help surgeons decide which nerve root is causing the problem before surgery is planned.

Facet Joint Injection

If facet joint inflammation or injury is the suspected cause of the low back pain, an injection into one or more facet joints can help ease pain and more specifically determine which joints are causing the problem.

During this procedure, a fluoroscope is used to guide a needle directly into the facet joint. The facet joint is then filled with a medication mixture. If the injection immediately eases the pain, it helps confirm that the facet joint is a source of pain. The steroid medication will reduce the inflammation in the joint over a period of days and may reduce or eliminate your back pain.

Trigger Point Injections

Injections of anesthetic medications mixed with cortisone are sometimes administered directly into the painful points of muscles, ligaments, or other soft tissues near the spine. These injections can help relieve back pain, muscle spasms, and tender points in the back muscles.

Prolotherapy

Injections of a dextrose-based solution into joints that are moving too freely can be used to stimulate temporary, low-grade local inflammation at the problem area. This initiates a subsequent healing cascade and scarring at the joint, which appears to ‘tighten’ tissue in the affected area. Prolotherapy is not generally performed under fluoroscopy.

Surgery

Surgery for low back pain is, in most cases, a last resort for treatment, except in the case of cauda equina. Surgeons generally prefer that patients try nonsurgical treatments for a minimum of three months before considering surgery. Fortunately, most people with back pain gradually get better with physiotherapy. Even people who have degenerative spinal changes tend to gradually improve with time. Only 1-3% of patients with degenerative lumbar conditions typically require surgery. In some stubborn cases of severe back pain that are not improving with physiotherapy, surgery may be recommended.

In some rare cases, your doctor may need to perform immediate surgery if you are losing control of your bowels and bladder (cauda equina syndrome) or if your muscles are rapidly becoming weaker. If these conditions develop, surgery is imminently required to remove pressure from specific nerves in your lower back before they become permanently damaged.

There are many different operations that are performed for back pain. The goal of nearly all spine operations is to remove pressure from the nerves of the spine, stop excessive motion between two or more vertebrae, or both. The type of surgery performed depends on each patient's conditions and symptoms.

Laminectomy

The lamina is part of the bony ring of the spinal canal. It forms a roof-like structure over the back of the spinal column. When the nerves in the spinal canal are being squeezed by a herniated disc or from bone spurs pushing into the canal, a laminectomy removes part or all of the lamina to release pressure on the spinal nerves. This is sometimes called a posterior decompression surgery.

Discectomy

When the intervertebral disc has ruptured, the portion that has ruptured into the spinal canal may acutely irritate or compress the nerve roots. This may cause pain, weakness, and numbness that radiates into one or both legs. The operation to remove the portion of the disc that is pressing on the nerve roots is called a discectomy or microdiscectomy. This operation is performed through an incision in the low back immediately over the disc that has ruptured and is one of the most common types of surgeries used to alleviate back pain.

In the past, spinal surgery required a large incision down the affected portion of the spine. Fortunately, spine surgeons can now perform most discectomy procedures through very small incisions in the low back. These surgeries are called minimally invasive surgeries. The obvious advantage of these minimally invasive procedures is there is less damage to the muscles of the back and thus a quicker recovery. Many surgeons are now performing minimally invasive discectomies as an outpatient procedure where no hospital stay is required.

Lumbar Fusion

When there is extra movement between two or more vertebrae, the excess motion can cause pain due to the motion itself as well as irritation of the nerves of the lumbar spine. In these cases, if physiotherapy has not helped, a spinal fusion is usually recommended. The goal of a spinal fusion is to force two or more vertebrae to grow together, or fuse, into one bone. A solid fusion between two vertebrae stops the movement between the two bones and pain is reduced because the fusion stops movement and decreases the irritation of the nerve roots. There are many different types of spinal fusions performed.

In the past, the traditional operation to perform a fusion of the lumbar spine involved a procedure in which surgeons ‘decorticated’ the back surface of the vertebrae. Decorticate means to remove the hard outside covering of a bone to create a bleeding bone surface. Once this was performed, a bone graft was taken from the pelvis and laid on top of the decorticated vertebrae. Just like a bone fracture would naturally heal, the bone graft and the bleeding bone grow together and fuse to create one solid bone.

Unfortunately, spinal fusions in the past were not always successful, mainly because the vertebrae failed to fuse together in up to 20 percent of cases. Due to this common failure, surgeons began looking for ways to increase the success of fusions. Since metal plates and screws had been used to treat fractures of other bones for many years, surgeons explored the idea of using metal implants to help fuse spinal segments. The more firmly two bones can be held together while the healing phase occurs, the more likely the bones are to fully heal.

Major advances have been made in recent years in the development of metal rods, metal plates, and special screws that are designed to hold vertebrae together to aid spinal fusion. These new spinal fusion techniques are referred to as instrumented fusions because of the special devices used to secure the vertebrae to be fused. Today the most common type of fusion is performed using special screws called pedicle screws that are inserted into each vertebra and connected to either a metal plate or metal rod along the back of the spine. The vertebrae are still decorticated and the bone graft is still used to stimulate the fusion of bones as they heal. Metal cages are sometimes used to create space in the spine and hold vertebrae in place while natural bone healing and fusion occurs. Depending on the problem, surgeons may need to make a surgical incision in your back or they may need to perform the surgery from your abdominal area.